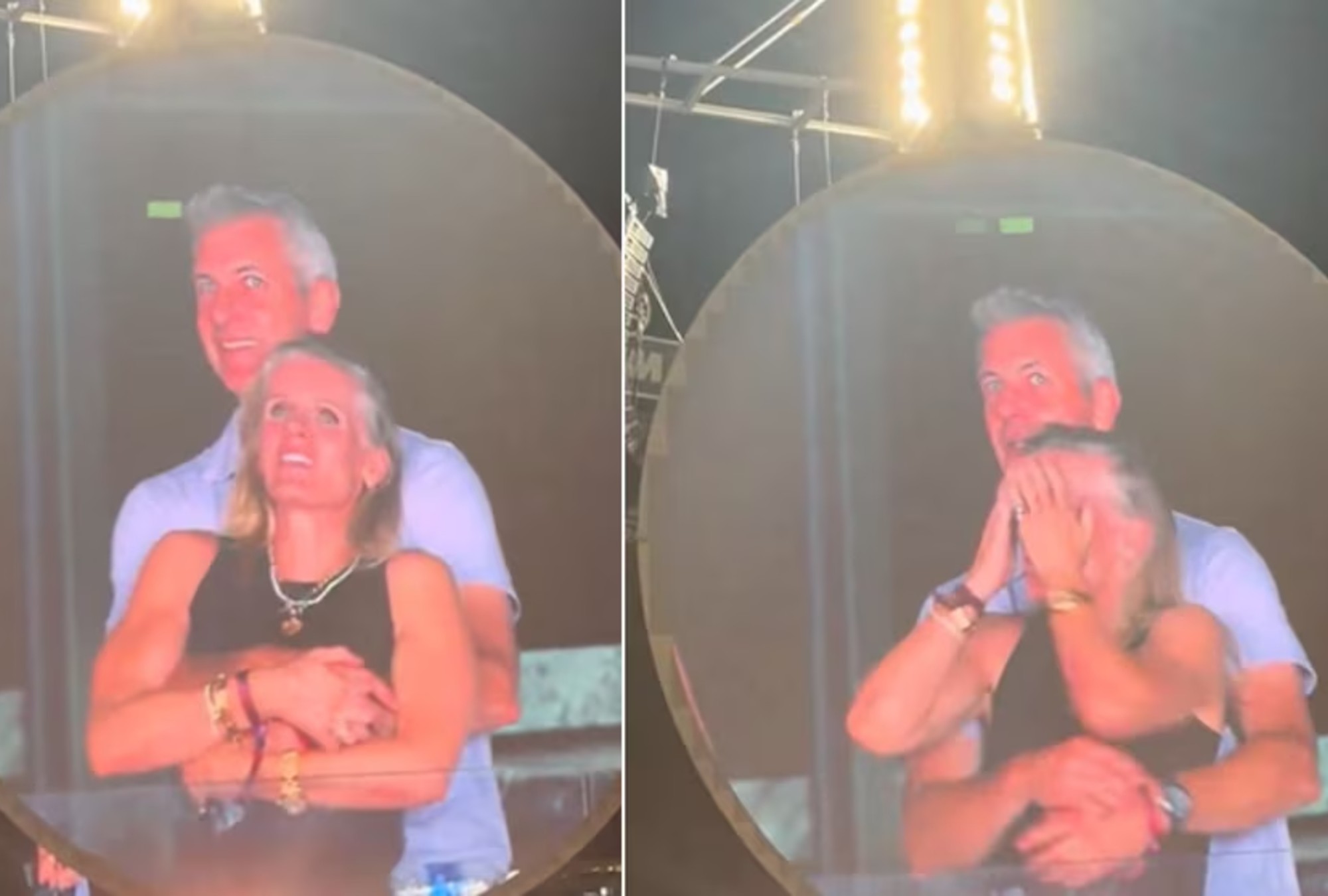

Andy Byron, CEO de la empresa tecnológica Astronomer, presentó su renuncia tras aparecer viralizado en la “kiss‑cam” de un concierto de Coldplay con la directora de Recursos Humanos. El incidente desató una crisis ética que terminó con su salida.

La exposición pública del momento íntimo, captado por la pantalla del estadio, generó una investigación interna y presión mediática. Astronomer cumplió una cláusula interna contra relaciones con subalternos y optó por separar al líder para proteger su reputación.

Durante un concierto de Coldplay en Boston, la popular “kiss‑cam” enfocó a Andy Byron y a Kristin Cabot, jefa de RRHH. Comentarios del vocalista Chris Martin como “¿Tienen un affair o son muy tímidos?” provocaron una oleada de memes, lo que catalizó la crisis pública de Astronomer.

La firma tecnológica colocó a Byron y Cabot en licencia administrativa y abrió una investigación formal. En cuestión de días, el consejo aceptó la renuncia del CEO para preservar los valores de la empresa.

Para saber más: La ‘kiss cam’ de Coldplay y el escándalo mundial de Andy Byron: lecciones en gestión de crisis

Ante la salida repentina del líder, el cofundador Pete DeJoy fue nombrado CEO interino. Astronomer inició la búsqueda de un nuevo director general, reiterando su compromiso con la ética y responsabilidad en el liderazgo.

Según el New York Post, Andy Byron cobraba entre 469 y 690 mil dólares al año, además de bonificaciones por rendimiento. Se estima que su patrimonio asciende a 50 millones de dólares y la valoración más reciente de Astronomer situó el valor de la empresa en 1,300 millones de dólares.

Sin embargo, no recibirá ese sueldo tras renunciar a su puesto directivo en la empresa.

Durante los primeros días, la empresa permaneció en silencio, lo que permitió la proliferación de memes, noticias falsas y cuenta de parodia, alimentando la narrativa pública con humor y desinformación.

Astronomer contaba con una cláusula que prohibía relaciones románticas entre jerarquías directas. Byron y Cabot la incumplieron, lo que permitió a la compañía tomar acciones disciplinarias claves para reafirmar su cultura corporativa.

Este caso pone en evidencia los peligros del desequilibrio de poder: decisiones sesgadas, favoritismo y daños a la confianza interna. El ejemplo refuerza por qué muchas empresas prohíben esas relaciones y aplican protocolos estrictos.

Algunos expertos en relaciones públicas señalan que, aunque no buscada, la crisis aumentó la visibilidad de Astronomer. Su rápido reemplazo del CEO y mensaje de valores corporativos bien implementado podrían ayudar a reposicionar la marca.

Casos precedentes como ejecutivos en Uber, Google o Starbucks muestran que una respuesta rápida, con medidas claras y consecuencias, suele ser más efectiva que excusas o dilaciones prolongadas.