Mónica Castañeda viene de una familia de artesanos por parte de su mamá y de sus abuelos maternos que se dedicaron a la producción y comercialización de rebozos. Toda su infancia, ella vivió rodeada de telares y empuntadoras, principalmente de su mamá y abuela.

Hoy esta emprendedora es propietaria de la marca Rebozos el Carmen, una empresa creada en 2019 de manera formal que se dedica a la venta de rebozos artesanales que se elaboran en Tenancingo en el Estado de México. También produce moda (capas, ponchos y gabanes) y accesorios (bolsas y collares) elaborados artesanalmente.

“De profesión soy contador público y en el 2018 me jubilé. Trabajé 26 años. Y, bueno, pensando en un proyecto decidí vender rebozos artesanales, sobre todo, para la exportación. Actualmente no exporto nada, pero vendo a través de redes sociales, Amazon y Mercado Libre”, expresa en entrevista Mónica Castañeda, directora general de Rebozos el Carmen.

La empresaria explica que por la pandemia por el COVID-19, algunos proyectos se quedaron estancados y ahora está tratando de retomar la exportación. “El mercado natural es Estados Unidos porque lo que comercializo es un producto de nostalgia porque hay muchos compatriotas que lo ven y dicen: “¡Ay es que mi mamá me arropaba con este rebozo!”, “es que mi abuelita tenía un chal igual a éste”

Para la dueña de Rebozos del Carmen, lo más provechoso ha sido el uso de redes sociales. “La situación por el covid no me afectó, más bien me hizo más fuerte porque impulsé mucho más lo que es la venta en plataformas tecnológicas”, asegura.

Hoy Mónica trabaja con alrededor de siete diferentes telares para poder elaborar prendas de diferentes colores y de buena calidad. “Me apoyo en dos empuntadoras, dos bordadoras y dos costureras. Todas estas personas no trabajan directamente conmigo, pero a raíz de la pandemia, me apoyé en ellas”.

Lo más difícil que ha enfrentado es la cuestión de la exportación porque, aunque ha viajado y tratado de colocar su producto en el mercado extranjero no ha logrado exportar. “Para mí ha sido el punto más duro. He tenido varias entrevistas, pero como mi producto es artesanal yo trato de ubicar a los clientes cuando me preguntan: ¿Cuál es tu capacidad de producción? Yo les digo que 200 piezas al mes. Para ellos es poco, pero realmente es un trabajo maratónico hacer 200 piezas porque es una artesanía”.

El proceso de elaborar un rebozo -explica- es de tres meses en promedio en el telar más un mes y medio el empuntado. Es un periodo largo y eso detiene la capacidad de producción. “Pero no puede ser de otra forma”, afirma la entrevistada.

Mónica Castañeda, propietaria de Rebozos el Carmen, comparte lo que ha hecho para lograr tener un buen negocio que produce rebozos bellos y muy finos. El más barato cuesta alrededor de 1,000 pesos.

1. Siempre estar innovando en los productos

Hay que pensar en cómo puedes hacer que las nuevas generaciones compren, en este caso, los rebozos. A Mónica le encanta modificar su producto principal que es el rebozo, y, por eso, le hace cambios desde el trabajo en el telar hasta que lo termina la empuntadora.

2. Insistir y buscar canales de venta novedosos

No importa si existe recesión económica o si la pandemia por covid llegó, posiblemente llegue otra -dice la entrevistada-. Hay que seguir insistiendo y buscando los canales de venta que son novedad para las nuevas generaciones. Que son la gente que están allí moldeando la nueva forma de hacer comercio y comprar productos.

3. Aliarse con un buen equipo de trabajo

La gente se compromete contigo, si tú te comprometes con ellos. Es la forma del éxito. “Yo me siento exitosa porque la gente con la que trabajo, lejos de juzgarme si no estoy exportando, agradecen el que yo les dé un empleo. Esto es esencial”.

En el futuro ésta emprendedora se ve precisamente exportando sus rebozos a través de un intermediario. Además, desea seguir ayudando a su comunidad de artesanas, sobre todo, porque más del 50% de ellas ya son adultas mayores. También, está muy contenta porque su familia se ha reactivado en la producción y comercialización de rebozos.

“Desde niña viví alrededor de los rebozos. Sin embargo, mis papás siempre me dijeron que tenía que estudiar una carrera. Todos mis hermanos y yo somos profesionistas y ya nos hemos ido retirando. Ahora vemos en los rebozos una alternativa de hacer algo diferente a lo que hicimos toda la vida”, expresa la empresaria.

La mamá de Mónica Castañeda tiene 87 años y está muy contenta porque volvió a empuntar sus rebozos a pesar de tener un problema de artritis severo. También su hermana mayor está haciendo capas y su cuñado es dueño de uno de los telares. Y ya hay otra hermana que está interesada en vender rebozos. “Mi familia se ha vuelto a reactivar en el medio del rebozo y derivado de eso tenemos mucho trabajo. Me siento muy satisfecha”.

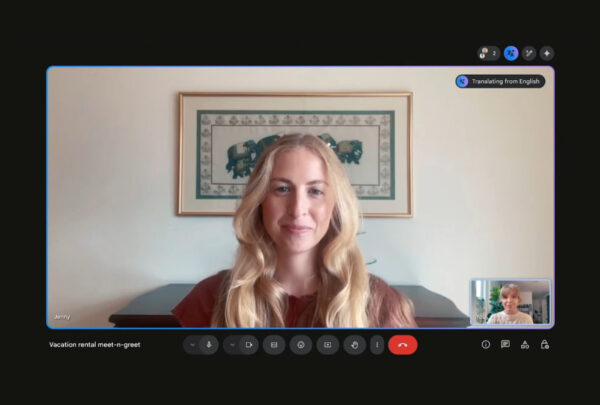

Las plataformas tecnológicas han ayudado significativamente a Mónica Castañeda, directora de Rebozos el Carmen. Una de ellas es CoDi® (Cobro Digital), una plataforma desarrollada por el Banco de México para facilitar las transacciones de pago y cobro a través de transferencias electrónicas, de forma rápida, segura y eficiente, a través de teléfonos móviles. Lo anterior en un esquema 24/7. Y lo más importante, ¡sin ningún costo!

Cualquier persona (física o moral) puede ser usuario de CoDi®. Ya sea el público en general; pequeños, medianos y grandes comercios, que quieran realizar un pago o un cobro a través de una transferencia electrónica.

Para cobrar con CoDi®, lo primero es validar tu cuenta. Aquí te decimos el paso a paso: